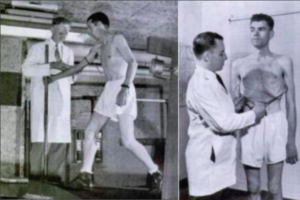

Content warning: contains images of malnourished individuals from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment

There’s an app for everything nowadays. Be it online banking, social media, or tracking a menstrual cycle, technology is having an increasing impact on the way we live our lives.

And it often gets a bad rap with mental health — Google it, and you’ll find many articles from influential organisations such as UNICEF and Forbes detailing their extensive research into the relationship between technology and poor mental health.

“Sarah”, an18-year-old Sydney resident, was diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa and Body Dysmorphic Disorder at age 13. Surrounded by pictures her friends shared online and following the Instagram accounts of ‘super models’ gradually took its toll. “Sarah” felt pressured to edit her photos so her body looked thinner, and judged what other people thought of her based on the number of ‘likes’ she received on a photo.

“I feel like eating disorders are massively misunderstood, especially in the media,” she said. “There’s this weird narrative in society that makes people seem content to stop the conversation at blaming a kid’s use of technology. There are just so many other factors that contribute to developing this kind of mental health issue.”

Mind Plasticity Clinical Psychology Registrar, Angelique Ralph, agrees that social media can skew the standard of what a healthy body looks like. ‘Body positivity’ hashtag movements like #bodypositive and #Effyourbeautystandards are still outweighed by posts that are heavily altered.

“I wish we could monitor it more closely,” Ralph said. “It needs more regulation… As a clinician, I have seen the negative effects [of social media] on young girls and boys, and also men and women. It’s not to say that [unrealistic beauty standards and eating disorders] wouldn’t have existed without the internet but there’s definitely a culture now.”

Particularly with the increased accessibility of information online, the psychology registrar and eating disorder specialist emphasised the danger of misinformation and taking health advice from people who do not have the appropriate qualifications. Calling yourself a ‘specialist counsellor’ or ‘life coach’ does not mean you are a registered clinical psychologist, she said.

Nevertheless, Ralph said she believes that technology is ultimately a double-edged sword. Apps like Recovery Record prove to be a strong argument against the narrative of a toxic online environment and are starting to take over the Australian scene in eating disorder treatment.

“Five years ago, I didn’t know anyone who used [Recovery Record],” she said. “Now most clinicians I know do.”

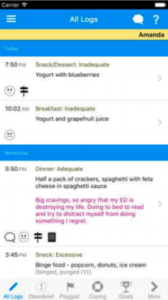

The Recovery Record app allows clients to keep both a ‘food diary’ and ‘thought log’ in real time and adhere to meal plans health professionals have assigned to them. It streamlines this information across multiple practitioners and allows psychologists to gain insight into the lives of their clients outside the therapy room, thereby bettering the effectiveness of time spent in face-to-face treatment. According to the creators, The Recovery Record system has attracted more than 10,000 eating disorder treatment professionals and 500,000 people living with eating disorders worldwide.

“It can be like a diary but on your phone, so you don’t have to hide a journal anywhere or carry a bulky book around with you,” said ‘Sarah’. “Most people have their phones with them so no-one’s going to question you if you open it up after a meal… It really takes away a lot of the shame and makes me accountable for my behaviours.”

Source: Google Images

As self-monitoring is also a core component of the most evidence-based form of eating disorder treatment (CBTe), clinicians are finding they are more able to ethically collect patterns on eating disorder behaviour and unpack it with their clients. Recovery Record allows patients to log their meals and thoughts in real time and gives therapists like Ralph a more accurate insight into their lives.

It also grants psychologists the ability to review their client’s logs before a session so they can come prepared and make the most of the time. This is especially useful for patients who are limited to 10 individual sessions per year on the Medicare Mental Health Plan, or for those who either cannot wait or may not be eligible for the 60 Medicare-funded sessions of treatment commencing in November this year.

“As someone who is now financially independent and has been suffering with an eating disorder for several years, I really need more than one session every six or so weeks,” said ‘Sarah’. “The app is actually a great and much less stressful compromise.”

Apps such as Recovery Record are nevertheless no substitute for face-to-face treatment.

“They’re useful for keeping my clients accountable,” said Ralph. “But people don’t always tell the truth in regard to what they eat and what behaviours they engage in. It’s just the nature of the illness… [and] I need to work through it with them in our sessions.”

In the realm of research, at least, technology nowadays allows for more ethical conduct into the medical community’s understanding of the physical and emotional effects of malnutrition. Compared to the days of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment in 1944-45, knowledge and sensitivity in both treatment and discussion of the mental health disorder is on a positive trajectory.

Source: (WPHNA, 2005, p.6).

The ethics, privacy, and understanding of eating disorder treatment and research can, in some ways, be credited towards advancements in technology. The author reached out to Recovery Record for comment but did not receive any response.

***

If you or someone you know needs help with an eating disorder, contact:

– Lifeline: 13 11 14

– Kids’ Helpline: 1800 55 1800

Or click here to view ReachOut.com’s comprehensive list of eating disorder support services around Australia.