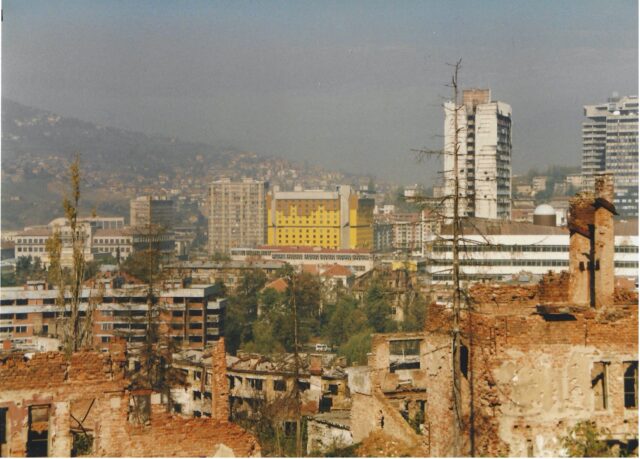

An early memory of growing up in Sarajevo flashes from my days in kindergarten less than a decade after the 1423-day siege the city came to be known for during the Bosnian war. Among the usual playing and sleeping, a part of our curriculum that stuck in my mind was our instructions on avoiding mines left over from the war, many of these yet to be cleared.

A white skull and crossbones over a red sign, with white writing shouting “PAZI – MINE”, watch out – mines, a harrowing image guaranteed to stay in the mind of a naïve child. It is also a poignant reflection of how the war of 1992-1995 influenced the lives of so many, and brought pain and suffering with the siege of Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. But the city did not give in to the terror and its people faced it with mental strength that helped them overcome the barbarity.

My mother was a 25-year-old student finishing her degree in Civil Engineering when war broke out on April 6, 1992. Serb aggression had followed Bosnia’s declaration of independence from the state of Yugoslavia in 1992, as it would mean a loss of territory. The rampant cultural division throughout the region between various ethnic groups became more tense as the years went by.

This realisation struck my mother as she sat on a bus coming from Serb-controlled Pale, a suburb in the eastern outskirts of Sarajevo where her friends lived. As armed Serb forces in uniform stopped the bus, her immediate association was with the World War II films depicting those same Chetnik forces, nationalist Serbs whose ideals clashed with those of a unified Bosnia and Herzegovina which sought to foster a multicultural state. She made it safely home to her mother and sister, and spent the rest of the day in tears.

Various forms of conflict, ranging from physical to psychological, characterised both the war and the siege. The psychological war waged on the citizens of Bosnia was not without its casualties – 150,000 deaths, as pointed out in Noel Malcom’s definitive work Bosnia: A Short History. In Sarajevo, daily shelling became common, with the list of those who lost their lives announced during the daily radio reports.

One of Sarajevo’s main streets became known as ‘sniper alley’ due to its openness, which meant anything living that passed through it would be a target for Serb snipers living in the hills overlooking the alley, including civilians. The siege allowed the Serb forces greater pressure and leverage over Bosnia. Food shortages and hunger became common throughout the siege. Regular daily activities became a death sentence to those who dared to attempt them. However, Ewa Anna Kumelowski would note that the citizens of Sarajevo did not give in easily, persisting in their efforts to get on with their lives.

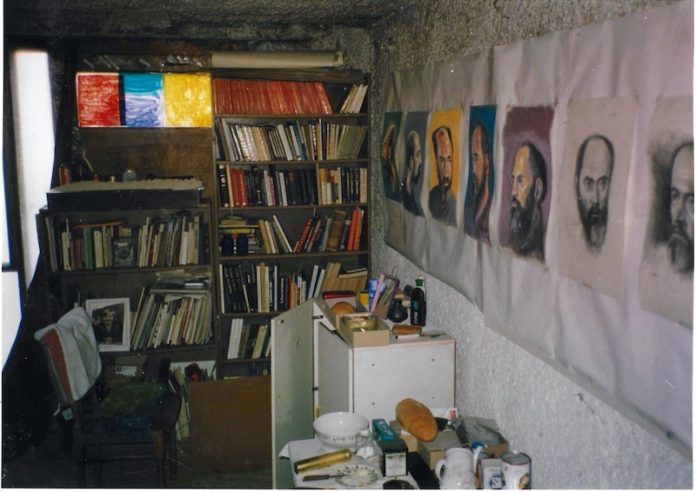

My mother described the basic activities she and her family focused on during the war: maintaining hygiene, reading books, and dwelling in the realm of art. The terror of artillery and sniper fire did not stop them from making sure they looked their best, because, as my mum put it, “If you already have to die, you may as well look nice”.

Despite the danger, mum’s friend, who played cello in the local string quartet, went to rehearsals every day. A local theatre organised plays and continued their work throughout the siege. A particular saving grace that helped my mother through the stress and turmoil was Thomas Mann’s Joseph and his Brothers, which characterised the solace she found in reading. This was partly due to the author’s riveting explorations of all the mind’s complexities, and partly the detachment from reality that granted moments of calm among the sounds of artillery fire. In her work Reading for your Life: The Impact of Reading and Writing During the Siege of Sarajevo, Natalie Ornat concluded that the act of reading provided a “mental armour” for those enduring the crisis.

While the citizens of Sarajevo may not have picked up rifles or fought on the front lines, these efforts were a defence against the siege and the barbarity of the war. The feeling one could rise above those pointing guns at them by giving in to the beauty of humanity through artistic expression was something no-one could take from them.

But food was essential for basic survival and my mother’s household became creative in their approach. Humanitarian aid provided bland carbohydrates during the war – pasta and bread. Sick of this diet by the time the war ended, they found ways of enriching these staples, combining different flavours from packets of foods arriving from overseas.

The story of the citizens of Sarajevo embodies the triumph of the human spirit. Through all the pain and suffering, while blood filled the streets art and creativity nourished the mind, providing a peaceful defence against adversity. To this day, the spirit of resistance lives in Sarajevo, and through the stories of countless citizens like my mother, we can understand what it means to fight for your humanity in the midst of destruction. The image of a skull and crossbones may bring distress and pain, but the beauty of art has the power to heal.