“It’s taken a lot of lamingtons and raffle tickets to get to where we are now.”

David Lewis is proudly patting an elaborate switchboard surrounded by turntables, microphones, and computer monitors. We’re standing in the main studio of Glen Innes’ community radio station in northern NSW, and I’m getting the grand tour.

The room’s large window reveals the rest of Radio 2CBD’s interior. On the other side, the walls are pasted over with peeling concert posters and laminated letters of appreciation. Wooden beams hold up the pointed roof. The cross embossed on the building’s face hints at its past life as a Baptist Church to the scattered traffic of the single-laned highway which cuts through the town.

It felt strange to be home again. After nearly two decades of living in Glen, I had left to study media in Sydney. Since leaving, my trips back had been sporadic, erratically determined by semester breaks and COVID waves.

But the more I have learned in the big smoke, the more I have been forced to look back to my country home.

The media plays a vital role in rural Australia: it informs and brings communities together, holds individuals and institutions accountable, and represents regional voices to the rest of the nation. However, regional media has faced huge challenges and undergone an immense transformation. A transformation that I have observed over the course of my life, yet only come to fully understand since moving away.

Growing up, it was easy to take the local press for granted; it was normal to see your own life reflected in the news cycle. I would mindlessly circle out spelling mistakes on the front page while my family discussed the deterioration of the local press. As corruption went unchecked and regional perspectives remained unheard, more of the news was read off our phones and less of it was about us.

There has been a sharp decrease in traditional news media across the country. With print journalism nearly halving over the last five years, the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance estimates that approximately 5000 jobs in Australian journalism have disappeared over the last decade.

Studying journalism online throughout the pandemic has been a poignant and ironic reminder of this technological and cultural shift.

It was only a month or so before this tour when, looking out of my window to the violet jacarandas of Sydney University’s eerily quiet campus, I composed an email to the local paper to request work experience. Tacked onto the wall beside me were photos of my family and the farm when the dams were dry, the paddocks were dust, and when glowing red lines of fire cut through the distant bushland.

Everything had come full circle as I put my thoughts together; I realised the importance of the press to connect these communities and I understood the existential challenges the industry faces. After all, the last time I read the paper it only had a few pages of local content which were heavily supplemented with the classifieds and articles from other towns. Most of its content was now centred on issues that didn’t affect us and people we did not know.

The local paper’s reply was short: their staff were working online, and the paper no longer had a physical presence in the region.

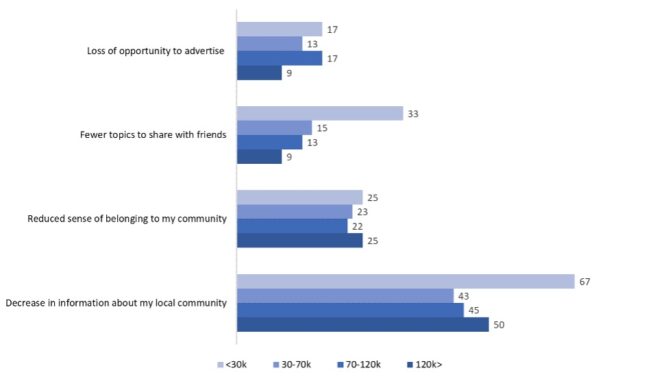

Across Australia, regional media outlets are closing their doors. The University of Canberra’s News and Media Research Centre, in describing “the local news crisis”, determined that in 2021 less than a quarter of regional Australians had a local news presence. Nearly one in five surveyed had experienced a merger or closure of their local area’s news service in the past five years. This spiralling centralisation, exacerbated by COVID-19, has had a profound negative impact on these communities reducing access to local information and undermining a sense of belonging.

After the paper was unable to take me on, I reached out to the radio station. David – one of 2CBD’s main coordinators – had generously offered to show me the ropes of community radio. “We are the only locally-based media organisation that has an office here in town now,” he says.

In Australia, there is a higher level of trust in local news. The loss of this coverage has consequently led to an increasing interest in emerging grassroots news services, be they online forums or stations such as 2CBD.

“At the moment we do broadcast local news, but it is ad-hoc,” David tells me. “But people will stop you and say that they didn’t know what was happening in relation to certain issues until they tuned in.”

Central to community radio is its reliance on volunteers and its non-profit nature. So, although community-led initiatives like Radio 2CBD now have a greater sense of responsibility, they lack a comparable level of professional knowledge and resources to supplant the lost journalistic presence in these areas.

“I firmly believe that community radio needs a lot more support to fill the gap that has been left,” David concludes.

After a few weeks of learning from, and supporting, the volunteer broadcasters at the station, I take one last look at the little brick building as I pull out onto the main road. In a couple of days I’ll be back in the city – a world away from the country town.

Just as I was welcomed by the community members doing all they can to keep local voices on air, I now know that as I continue my studies I cannot separate myself from what is happening to disperse and muffle rural stories. The knowledge of this complex crisis alone means that I have a duty to embrace my roots and speak up.

I reach over and turn on the radio in time to catch the welcoming address from one of the volunteer presenters I had passed on my way out. There is immense comfort in the knowledge of rural communities’ proven adaptability, strength and preparation to take on the challenges thrown at them.

Even so, it is impossible to not worry about what my next trip home will reveal.