The humid heat of the late afternoon hung heavy in the air. The chatter of magpies and noisy miners had abated. Even the rumble of traffic had ceased to exist as the world paused with bated breath, awaiting the arrival of a storm.

All was still. Except me, a lone girl tracking the footpaths of Sydney suburbia after another day at uni. That day in my biology class we had been learning about epigenetics.

I had always been interested in genetics, understanding how people were connected and shared traits inherited from their ancestors. But epigenetics, this was something new.

A fundamental unit in biology is DNA: a molecule stored in every cell of our bodies that contains a unique chemical code. Our bodies process this code to determine characteristics such as height, immune response, and even aspects of personality.

Until recently, science had believed that we actors in the great play of life closely followed the DNA script of DNA edited by evolution since the dawn of life on Earth. But the concept of epigenetics is beginning to change this, as studies suggest life experiences and the influence of one’s environment – especially in early childhood – impact what lines of our DNA script we are able to perform.

School days

The rumble of thunder pierced the stillness as I paused in front of a familiar building, my old primary school.

“Quickly, quickly! Two straight lines!” shouted Mrs C.

Her Year 5 students bobbed up and down outside the classroom, trying to get a first peek of the new kindergarten students they’d be buddying and guiding around the school.

I stood attentively at the front of the line, watching with anticipation. The small kindergarten students in their brand new, too big, uniforms filed into the classroom. Some merrily waved off their parents, while others wore worried expressions, apprehensive of their first day at ‘big school.’

A short distance from the classroom one of the kindergarten students clutched his mother’s hand. She stroked his head, and speaking in a soothing voice led him towards the classroom.

On approach the mother beckoned to the young kindergarten teacher, Miss A.

“My son is quite nervous about today,” she said, “is it okay if I sit with him in class for a little while?”

“No parents allowed!” snapped Miss A as she grabbed the boy’s free hand and began ushering him into the classroom.

Tears tracked the child’s chubby cheeks as he cried out. His mother went to follow him but was blocked at the door.

“He’ll get over it,” said Miss A. “If you have your child’s best interest at heart you won’t interfere. We know what we’re doing!”

The door slammed shut.

My class teacher Mrs C gave the mother a reassuring smile that said, “It’s for the best”.

Impact of early childhood stress

A gust of cold air shook me from my thoughts as the sound of wind rushing through the trees heralded the arrival of the storm. I quickened my pace.

The memory had reminded me of an epigenetic study discussed in my biology class.

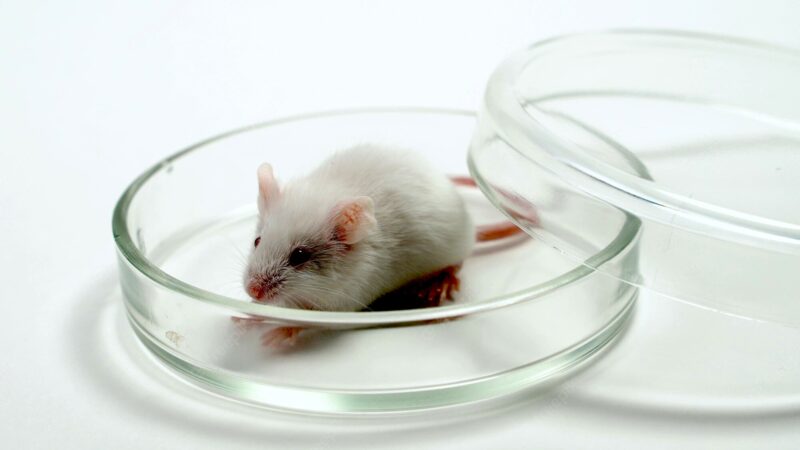

The study titled, “Early-Life Experiences, Epigenetics and the Developing Brain” by Drs Marija Kundkovic and Frances Champagne explored the impacts of early childhood stress on development. In the study, scientists mimicked the experience of maternal separation removing mice pups from their mothers in a stressful manner. These pups were monitored and found to produce elevated levels of glucocorticoid hormones related to the fight-or-flight response. They also showed increased anxiety behaviours.

When the pups had grown, male mice from the experiment were mated with female mice that had not been subjected to a stressful experience. The ‘father’ mouse was removed before the birth of the pups, preventing the modelling of any behaviours. The study found that the new generation of pups also presented higher than normal levels of stress hormones and anxiety behaviours.

These physiological changes occurred in the new generation of pups, even though they had not been personally exposed to the stress experience. Studies have found this can happen for up to two generations. Researchers have begun exploring this phenomenon in humans, both from the context of childhood development and transgenerational trauma such as in the descendants of Holocaust survivors and victims of slavery.

Histone Modification

Epigenetic mechanisms support these findings and operate in a myriad of ways. One key mechanism is histone modification. Imagine your DNA as a long multi-coloured thread. The different sections of colour can be thought of as different genes (segments of DNA that contain information about certain traits). For our body to process DNA information, the DNA thread has to be loose and accessible. If it is tightly coiled and knotted certain sections of colour (genes) can’t be accessed. The DNA thread is tightened or loosened during histone modification.

Histones are small proteins in our cells around which the DNA wraps, like thread around a bobbin. Experiences we have influence how loosely or tightly wrapped is our DNA. In the mouse study, sections of DNA that contained information to produce stress hormones were loose and accessible, while parts of DNA that produced calming hormones were tightly coiled and therefore inaccessible. This led the mice with a history of stress to produce more stress related hormones. How these epigenetic features of DNA are passed on between generations is still poorly understood and is being slowly unravelled by researchers world-wide.

If they knew, would they change?

I sighed inwardly. My mind compared the similarities between the mice in the scientific study and my memories of the kindergarten boy. My brother. He had developed anxiety at a young age and I wondered how much epigenetics had been involved.

The rich smell of wet earth reached me. I turned my head upwards and let the first few drops of rain wash across my face. Squawking, a flock of cockatoos passed overhead as the drizzle turned into a downpour. I made a dash for the nearby bus shelter and watched as steady sheets of rain washed away the heat of the day. I shivered.

Looking through the sheets of grey I could just make out my old primary school. I’d learned through my studies a biological basis for why early childhood experiences were so important. Watching my school, I wondered, if others knew what I knew, how would they change?