We walk, as a procession of ants, through the thick understory of the critically endangered Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub. The gleam of our head torches bounces with every step, making shadowy branches sway with more than just the chill wind. Beside us, flannel flowers float, a dusty white, in the darkness.

“Almost there,” the lead ecologist Rhiannon Khoury whispers, her eyes on the GPS device.

And then we see it. Purposefully hidden, tucked amongst tufts of plume grass: a small bark brown mammal nestled within the cage trap. Its eyes go large with our approach. And I hate to think how we must appear – large predators with suns strapped tight to their foreheads.

She is a bush rat. And wonderfully, her coat is glossy, and her hip bones are padded by flesh. “Very good”, I scrawl under the health condition column on the data sheet. With incredible speed and gentleness, the ecologist microchips her and takes a small genetic sample from her pearl pink ear.

Once locally extinct from this bushland, this little mammal has been given a second chance at North Head via the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) reintroduction program. And as a conservation science student, I feel immense happiness seeing her return. But to the outside watcher this very scene might appear very different. Inexplicable, cruel, or unnatural, perhaps.

Why would you do this? They might ask.

Restoration Ecology! Reply some.

Conservation Biology! Chime others.

But the hard truth is this: righting the ecological wrongs of the past isn’t so clear-cut. There is no definitive manual on how to save a species let alone how to reconcile all that pushed it from its habitat in the first place. And to me, nothing so exquisitely encapsulates this friction of purpose than the notion of de-extinction.

Previously the stuff of science fiction, de-extinction has traversed the realm of impossibility, empowered by the seemingly limitless potential of the gene-editing revolution. Under the banner of conservation, scientists and investors alike have become determined to bring back species we have let slip (or indeed pushed) away.

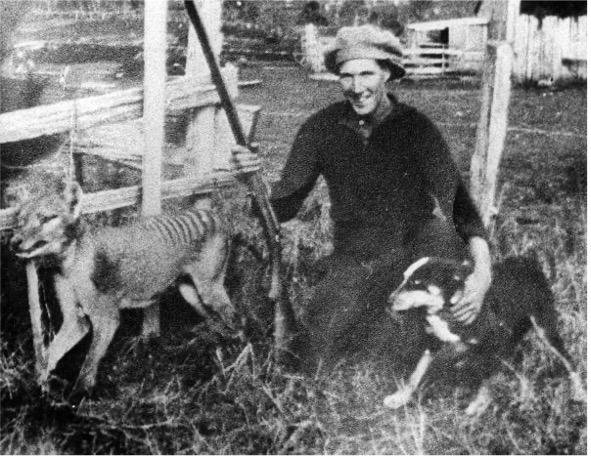

Standing in Sydney University’s Chau Chak Wing Museum, I come face to face with the animal first set to return via de-extinction: the thylacine, otherwise known as the Tasmanian Tiger.

The skull is lit from beneath and placed on a pedestal allowing the sweeping jawline and long canines to cast shadows on the wall behind. On the wall opposite, visitors can read its tragedy.

With much of its habitat cleared, the thylacine was forced onto newly converted agricultural land where locals hunted it viciously. The last remaining individual died at Beaumaris Zoo, 1936.

Lost was a species fundamental to its ecosystem. Indeed, locate the website of Colossal Biosciences, the company behind the de-extinction movement, and you will find a visual spectacular of sliding graphics showing the desertification triggered by the loss of top predators from an ecosystem.

Dr Andrew Pask, Professor of Biosciences at University of Melbourne and leading researcher on thylacine de-extinction, engenders a sense of obligation and presents an opportunity for absolution in a Sydney Morning Herald interview. “If we have the technology to bring it back,” he says, “we absolutely owe it to that species to bring it back.”

But behind the inspirational sentiments, billion-dollar celebrity endorsements and impressive interactive websites lies a lot of ambiguity.

Where will these resurrected animals live in such a radically changed landscape? And are the drivers of their extinction really gone? With few food sources, they would surely return to prey on farm animals. Would they then be kept in an enclosure only to become a lucrative tourist attraction?

With every question, the colourful aspirations of returning ecological function through reviving these long-lost predators turns deathly pale.

But the issue runs deeper than logistics. It seeps into the sticky and often painful consciousness of our Western capitalist cultures’ relationship with nature.

The concerns of Dr Christian Diehm, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, capture this perfectly. He writes: “[De-extinctions’] ideal is less a call for humans to scale things down to make room for other forms of life than it is a summons to keep scaling up our technological and managerial interventions in their worlds.”

And some, such as Dr Erik Katz who is Professor of Philosophy at the New Jersey Institute, even doubt a resurrected species holds ecological legitimacy altogether: “The new substitute entity is a product of human activity, not the result of natural evolutionary change.” Katz’s research focuses on environmental ethics, addressing issues such as which species should receive conservation priority over others when funding is so limited. Ultimately, he questions what our attempts to restore ecosystems, including ‘techno-fixes’ like de-extinction, are really trying to achieve.

A keen reader might begin to see a problem: if human actions severed nature, how can we aspire to use human intervention to reverse the damage? Is the locally extinct fauna the AWC restored as much a failing imitation of what once was as a thylacine born from a test-tube?

But as I look out over the sandstone cliffs of the North Head Reserve, I feel deeply what sets these conservation efforts apart from those of de-extinctions.

With the sun beginning to spray orange light over the ocean and only one more trap to process, we have made good time. From this vantage point, I can see most of the small pocket of the reserve as well as the multi-million-dollar real estate on the headland opposite.

“It’s crazy how much diversity can thrive when surrounded by so much urban development,” I say. “You almost forget you’re in Sydney when you are deep in the scrub!”

“I used to think the same,” the lead ecologist replies. “When we first decided to try re-introductions here we needed to remove the invasive black rats that infested the area. Being so close to the city, we worried they were just going to keep returning to dominate the landscape excluding all the native animals and stopping them from feeding.”

But this did not happen. Instead, the native rats were fiercer and better adapted to defend the bushland territory, and due to this the fate of the other species returned looked considerably brighter too.

Species like the brown antechinus that sits, nose twitching, in the lucky last trap of the survey. As a member of the Dasyuridae family, this antechinus is a living relative of the thylacine. While much smaller, it has an elongated jaw equipped with prominent canines. Its pointed red brown face is framed by an explosion of whiskers.

Samples and measurements completed; we release the little marsupial into the grasses.

As I hand the datasheet clipboard over, now muddied and crumpled at the edges from a week in the field, I ask Khoury the ecologist what will be done with the information gained.

“We’ll check for inbreeding and other population health markers. And eventually, there will be some research done to look at how the pollinators are affecting the plant community.”

“Pollinators?” I ask.

“The antechinus and the pygmy possums we re-introduced will hopefully improve the health of the critically endangered Banksia Scrub,” she replies.

In this awareness of what once was, the intricate ecological interactions of hundreds of plant and animal species, the answer to what role conservation should play in this radically changed world emerges.

Not prissy about the pristine but profoundly attentive to what we have done to force such losses. And recognising that the ecological devastation enacted on this land is part of a wider fabric of colonial atrocities– of the ripping of the ecosystems from the traditional custodians who so intimately knew and cared for them.

It is from grieving and learning from this reality that conservation has the best chance to return self-sustaining integrity to these ecosystems.

Maybe de-extinction has one gift to offer this world in biodiversity crisis: a keener awareness of what we stand to lose. And, perhaps, a realisation that what is lost, is gone forever.